Tenured Radical has the second in her three-part series on single-sex education for women at her blog, “Feminism’s Unfinished Agenda: If Women Have Equal Opportunity, Why Are The Outcomes So Very Unequal?” There’s a lot of food for thought, but I thought I’d highlight that she features some reminiscences of Harvard University President Drew Faust of her student days at Bryn Mawr under President Katherine E. McBride:

I will never forget Miss McBride up on the stage telling us to be humble in face of Our Work. I had not before realized that I had Work. I had thought I did assignments and took tests and wrote papers. But Miss McBride’s address instilled in me a new found reverence for learning and scholarship. My awe at being invited to play even a small part within that sacred and timeless world has never left me.

I’m with Drew Faust, although I followed her by more than 20 years in the late 1980s, when the United States–when it contemplated feminism at all–was already slipping deep into its “post-feminist” delusions. Like I said a few days ago: we were taken seriously, so we took ourselves seriously. We didn’t have the luxury of holding back in class discussions and letting men take the lead. We didn’t have the pressure of heterosexual performance in an academic setting (mostly–Haverford women and men could and did enroll in most of my classes over my four years, so an entirely single-sex classroom was probably a rarity.) I and my classmates wrote the student newspaper, ran for the Honor Board and for student government, and competed against each other for scholarships, prizes, internships, and honors. It was a great laboratory for women’s leadership and (mostly) friendly competition.

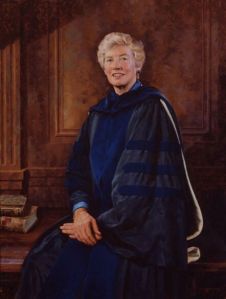

I never knew President McBride–Mary Patterson McPherson, a woman even taller, blonder, and more regal than McBride was president of the college when I was a student. But her convocation addresses–both at the start of the fall and winter terms–were not to be missed. They were always passionate–about contemporary politics as I recall (these were the Reagan-Bush I years) as well as the life of the mind and the value of a Liberal Arts education.

I used to wonder why all Bryn Mawr Presidents (save for the lone rooster in the 20th century hen house, Harris Wofford) had to be Scottish giantesses who read Greek. (I knew I would never qualify, so that took the pressure off.)

“I used to wonder why all Bryn Mawr Presidents…had to be Scottish giantesses who read Greek.”

I imagine the ability to be regally intimidating is a necessary quality for presidents of women’s colleges.

LikeLike

Heh. The new President (McAuliffe) has a Scots last name, although I don’t know how she came by it, and she’s blonde. She’s not nearly as tall as Mary Pat is–but then, no one is.

I’m only 5’5″, at least 7-8 inches below Presidential height, I think. .

LikeLike

McAuliffe is an Irish name, me thinks.

LikeLike

Her posts are good particularly in that they remind one that one goal and supposition of these colleges was that one wouldn’t have to get married for financial reasons, and that one’s work was real.

This was also true at the large state university I went to from 1974 (freshman) to 1987 (PhD) — the pressure not to take oneself seriously came from home, not from school, and from my parents, not my grandparents, great aunts and uncles and so on, all of whom had been born in the 19th century.

I didn’t find out about women afraid to participate in class discussion because of not finding men and so on until I started working in a SLAC filled mostly with people from the East.

That was in the late 80s and so it fits with the postfeminist delusions and so on. Now most of my students are women, because I teach literature and men don’t seem to study that here too much, so it’s like having a women’s college inside a big university.

I still think though that it’s home not school that forms peoples’ attitudes. I don’t know, maybe a small women’s college would have been yet more super therapeutic for me than regular college. Serious therapy about my sexist parents would have been helpful.

But it all sounded so precious and goody-goody at the time, and family-esque, and I wanted to go into the world, and not have to have a mentor.

This is not to say I don’t mega-admire those colleges and all.

LikeLike

There is one more or less exclusively female institution that no one here has mentioned — nursing school. My mother was an RN, because her mother told her that if things didn’t work out in marriage or if she were left a widow, she could always make a living as a nurse. It worked out for her, too.

LikeLike

Sorry about the misidentification of the surname, FA. I don’t know my Macs from my Micks, as it were!

Z, I think you’re right that family matters a lot. Different students benefit from different learning environments–there is no one right way to educate a young woman.

And, Jack–you’re right that nursing is still very female-dominated. But I know a lot of dudes who are nurses, in part because it’s an in-demand field but also in part I’m sure because I live 1/2 a mile from the big nursing school in my state.

LikeLike

Z makes a good point about family and “feminist” upbringings can come in the most unlikely settings. My mother was hard-core evangelical Christian (submit to your husband type Christian); my father is liberal politically but pretty old (for my age) so his liberalism has limits. I wasn’t allowed to hang out with friends or boys or go to dances for fear that I fall into sin and disrepute. I’m not exaggerating.

But, when I read these posts about women’s ambitions being squashed, I realize that for all my parents’ flaws and restrictions, I somehow managed to grow up thinking I could do anything. It wasn’t feminist per se, in that I don’t ever recall being told that I could do anything as a woman. My parents just didn’t make the distinction. In their minds, I was smart enough to do anything I set my mind to and there were no obstacles to my success unless I put them there. College was about getting a career and a profession, not about getting married. (My mother would have been devastated if I’d gotten married in my early 20s.) My mother wouldn’t have supported my going to a women’s university, which was fine. I didn’t want to go to one. But I think part of her reservation probably would have been along the lines that I could compete with anybody so why pretend otherwise? (I recognize that that’s a misreading of women’s universities; I’m just explaining her logic.)

And, in another thing that seemed minor at the time but has turned out to be a pretty big deal, my mother encouraged my platonic friendships with boys in my classes. There were probably about 4 or 5 guys that I was good friends with in high school. So I’ve always seen myself as equal to them and colleagues, etc., rather than view every single guy as a potential romantic possibility. It always struck me as normal but a few years ago, I was at a workshop type thing in my graduate program and was shocked to hear some of the women saying that they were intimidated about talking to some of the male graduate students in our program about their work because it might be seen as flirting. (One woman went so far as to say that this worry of hers didn’t stop until she got into a serious relationship herself.)

So yeah, you can find feminism in strange places.

LikeLike

This was exactly PhysioWife’s family context, and she has reached the six-sigma highest reaches of her profession.

LikeLike

Woodrow Wilson sort of wondered the same thing; why just being Scottish, and 5-11, and having some clearly regnal impulses wouldn’t get the job (done). So he headed over to Tigertown, USA, after a few years at Bryn Mawr.

I was a few years behind Drew Faust at BFU and in a different department, and, while no one can really “seem like a future president” of anything, much less Harvard, in a graduate seminar, she definitely had her stuff together while us callow first-years were trying to figure out how to spell the names of campus buildings, or what the heck an “AHA smoker” was. (A term that the prof-staff would drop into conversations with knowing

looks). I wondered about the Haverford exception in the above post. Because my understanding of the single-sex benefit would have presumed that it needed to be pretty much absolute. Did the ‘ford longhorns tend to behave differently depending on whether they were playing home or away? Or did you ever go down the road to find out?

My mother went to a (Catholic) all-women’s college, and definitely emerged from there with a don’t need to wait for, or on, the menz, perspective on the world. Although I was way too clueless to ask or even wonder about any possible connection between those things when I still might have found out.

LikeLike